운무

雲: 구름 운

霧: 안개 무

- 구름과 안개

- 사람의 눈을 가리고 또는 흉중을 막고, 지식(知識)이나 판단(判斷)을 흐리게 하는 것의 비유(比喩ㆍ譬喩).

Cloud and fog

日: うんむ [unmu]

中: 云雾 [yúnwù]

운무

雲: 구름 운

霧: 안개 무

Cloud and fog

日: うんむ [unmu]

中: 云雾 [yúnwù]

소복

素: 본디/흴 소

服: 옷 복

White clothes (traditionally worn during a funeral in Korea)

日: そふく [sofuku]

中: 素服 [sùfú]

착복

着: 붙을 착

服: 옷 복

embezzlement, (formal) misappropriation, embezzle, (formal) misappropriate

日: ちゃくふく [chakufuku]

中: 侵漏 [qīnlòu]

Almost everyone around the world have been quarantined at home, and it’s a perfect time to brush up your skillsets. Let’s take a look at this word, 硏磨 (to grind, study, or research). 硏 refers to an inkstone, which is a flat stone. What do you normally do with an inkstone? It’s used to grind ink. Once ink is ground and contained, you would write with it. Writing is associated with studying and researching, therefore you have a process from grinding of ink to writing, where you would be studying or researching, so we have all of these meanings associated with this character 硏.

With 磨 (to grind or rub), we have a compound of 麻 (hemp) and 石 (stone). So, the character was for an act of using a stone-based tool to soften or decorticate hemp stalks. It was done by either grinding or crushing the stalks, so we have both of these meanings associated with this character. When an object is either grinded or pounded, it wears out and it can even disappear eventually. So, 磨 can also mean suffering, being worn down, or disappearing after being worn down.

Combining above meanings we can think of the meaning of 硏磨 as an act of studying and researching until the subject (who would be studying and researching) would disappear from being worn down so much. We can associate a degree of pain with such an act, and there is a sense of constant repetition. Therefore, there can’t be 硏磨 without difficulties and repetition. Such process is needed in order to improve our skills and talents.

Even in English, the informal use of the word grind is associated with working or studying laboriously. So, it’s interesting to see that we have such commonalities both in the East and the West.

Source: https://www.donga.com/news/List/Series_70070000000757/article/all/20060104/8262972/1

Update and English translation by Michael Han (https://michaelhan.net)

Many people set New Year’s resolutions, but it isn’t easy to follow them through ’til the end of the year. Why is that? It’s because people aren’t determined enough to put that much effort into it. Why do so many find it difficult to put that effort in? It’s because they are anxious to reach it quickly. When we set out to achieve something in the future, it’s important to be diligent and persistent in order to reach a completion.

There’s a phrase 行百里者半九十. 行 originally meant an intersection, or a junction of two roads. This is where we get the meanings such as procession, or degree of relationship, as in 行列. There were many merchants at such junctions, so we also have words like market, or merchant. 銀行 (bank) consists of the word 銀 (silver), so it originally meant a place where you bought and sold silver. In the past, silver was used as a form of common currency. 洋行 means a Western-style store, or a new type of merchant. Many people walk about a junction on a road, so we also have meaning of going or moving around. In 行百里者半九十, 行 means going. Therefore 行百里者 means a person going one hundred ri.

半 originally meant half, but here it means considering as half. We just have number 九十 for a numeric value of ninety, but because of the word 百里 (hundred ri), we can assume the unit of ri here as in ninety ri. So, 半九十 would mean consider as ninety ri as half.

Synthesizing these together, we have, “a person set out to travel one hundred ri goes ninety ri and considers it a half of his journey.” With such attitude, the person will continue on with persistence, and will not be so anxious to get to the destination quickly.

A turtle has short legs, so it can only travel at a very slow pace, but don’t forget that it can also travel 1,000 ri.

Note: ri is roughly about an one-third of an English mile.

Original: https://www.donga.com/news/Culture/article/all/20040104/8017106/1

English translation by Michael Han (https://michaelhan.net)

原: 秋水/2 中 + 後漢書, 馬援傳, 等等

井蛙不可以語於海者,拘於虛也

同: 井蛙, 井底蛙, 埳井之蛙

井中之蛙 (정중지와, jǐngzhōng zhī wā, かんせいのあ) well / in / [of] / frog

A frog in a well. Referring to someone with a very narrow view of things due to ignorance. It comes from the saying, “a frog in a well doesn’t know about the great sea (井中之蛙 不知大海).”

This was near the end of Sin dynasty (新) which appeared after the end of Western Han dynasty (前漢). Wehyo (隗囂) of Nong-seo (隴西) maintained his relationship with King Gwangmu (光武帝) as an ally, but as King Gwangmu became more powerful he felt uneasy, and tried to form an alliance with Gongsonsul (公孫述) of Chok (蜀). Around that time, Gongsonsul had founded a country called Seong (成), and was calling himself an emperor (皇帝). The land of Chok was rich in natural resources, and the terrain made it a natural stronghold, so it was perfect to build up his power.

Wehyo decided to send Mawon (馬援) to Chok in order to find more about Gongsonsul. Mawon was born in Mureung (武陵) and he had moved to Nong-seo to avoid troubles after Wangmang (王莽) had died. After the move, he had accepted the request to become an advisor to Wehyo. Mawon was also a childhood friend of Gongsonsul.

Mawon eagerly looked forward to being received with a warm welcome by Gongsonsul, but he was met with a cold reception. Gongsonsul had been a king for four years, and he assumed a haughty attitude at the top of the stairs, and tried to give Mawon a government position. Of course, Mawon quickly made an exit and returned.

“The supremacy under heaven is yet to be decided, but instead of showing utmost courtesy to a capable person for advice on running a country, he only shows his haughtiness. One cannot discuss affairs of this world with such a person. He is a prideful frog inside of a well. It’s better to look to the East for going forward,” said Mawon to his entourage.

Mawon also said the same thing to Wehyo, and added, “He is merely a frog inside a well. You do not need to deal with him. I think it will be better to be more expectant from Han (漢).” With this, Wehyo gave up trying to form an alliance with Gongsonsul, and instead formed an amiable relationship with King Gwangmu, who would be the progenitor of the Eastern Han (aka Later Han.)

The expression “a frog in a well” was already widely in use before Mawon had used it. There is this narrative in Jang-ja (莊子): “A frog in a well can’t talk about the sea because it is inherently limited by the place (墟) it lives in. A summer bug wouldn’t be able to talk about ice because it only knows about the season of summer. You can’t talk about the Way (道) with someone who only knows about one thing because he is restricted by the limitation of his own learning.

原: 則陽/4 中

「有國於蝸之左角者曰觸氏,有國於蝸之右角者曰蠻氏,時相與爭地而戰,伏尸數萬,逐北旬有五日而後反。」

蝸牛角上爭 (와우각상쟁, wōniú jiǎo shàng zhēng, 蝸牛角上の争い (かぎゅうかくじょうのあらそい)) snail / horn / above / fight

A fight of snail horns. A useless fight or strife in a small world.

During the Warring States period, feudal lords battled each other year after year for hegemony. The story comes out during such tumultuous time.

King Hye (惠王) of Wi (魏) formed an alliance with King Wi (威王) of Je (齊), but later, King Wi broke this agreement. King Hye was outraged over this, and wanted to send an assassin to kill King Wi. The ministers of the court considered it cowardly to send an assassin, so some suggested to wage war instead, and some suggested against it. In midst of this, Hwa-ja (華子) suggested just the thought of waging war itself is wrong.

Hwa-ja came forward to the King and spoke, “All these suggestions are not good. Anyone who points to people discussing these matters and regards them as people who are putting the country into a turmoil, are themselves people who are throwing the country into confusion.”

King felt frustrated and asked, “What do you suggest that we do, then?”

“We have to put aside quarrelsome arguments (是非) and stand on the side of the Way (道).”

The King drew a blank stare, and then the chancellor Hye-ja (惠子) called upon a sagacious person named Dae-jin-in (戴晉人) and had him stand in front of the king. He first asked the king a question.

“Do you know what a snail is?”

“Yes, I do.”

“On its left horn is a country of Chok (觸氏; “pierce”) and, on its right is a country of Man (蠻氏; “barbaric”), and they were fighting each other to expand their territory. There were several tens of thousands of people dying. There were times when it took 15 days to just pursue fleeing enemies.”

The king was dumbfounded at this story, and Dae-jin-in asked another question.

“Do you think there’s an end to this world?” The king shook his head. Dae-jin-in continued.

“Then to those who ponder on this limitless world, the existence of these countries can only be trivial.”

He was basically saying that whether it’s the country of Wi, or the country of Je, they were both like countries on top of a snail’s horns from the perspective of someone whose mind ponder on great things such as the limitless universe. Dae-jin-in asked this question and left the king.

“What difference are there between you, who is wondering whether or not to wage war against Je, and Chok and Man on the top of the snail horns?”

原: 莊子, 秋水/1 中

望洋之歎 (망양지탄, wàng yáng zhī tàn, ぼうよう-したん), look / sea / [then] / sigh

Sighing after looking at a great sea. Admiring another’s greatness, and feeling shame over one’s shortcomings.

Long time ago, at a place called Maeng-jin (孟津) on the midstream of the Yellow River (黃河) lived a god (河神) named Ha-baek (河伯). He was impressed with the golden gleam of light reflecting from the river, and said, “There is no other body of water like this in this world.”

A voice replied, “No, that’s not true.” Ha-baek turned his face to find an old turtle nearby, and asked.

“Is there a body of water greater than the Yellow River?”

“Yes. Near where the sun rises is the North Sea (北海, now known as 渤海), and it is said that all rivers flow into it. So, the breadth and width of that place is many times greater than the Yellow River.”

Ha-baek shook his head in disbelief. He had never left Maeng-jin, and he couldn’t believe the words of this old turtle.

“How could such a big body of water exist? I can’t believe it unless I see it myself.”

Then autumn came. The Yellow River rose very high due to many days of rain. While watching this, Ha-baek was suddenly reminded of his conversation with the old turtle, and decided to follow the river to see the North Sea himself.

When Ha-baek reached North Sea, a god (海神) of that place named Yak (若) came out to greet him. He raised his hands and cut through the air to calm the waters, and before them was a horizon of water that stretched far beyond what Ha-baek had ever seen before.

Ha-baek was taken aback by the breadth and width of what he was seeing, and his jaw dropped. He was ashamed of his past ignorance and said to Yak, “I heard of the greatness of North Sea, but did not believe it until now. If I did not see this here today, I could not have understood how little I had seen and known in life.”

Yak smiled and said, “You were a frog in a small well, weren’t you? Without coming to know about the great sea (大海) you would’ve been recognized as a god with little knowledge of the world, but now you have managed to get yourself out of such place.”

原: 莊子, 逍遙遊/1 中

鵬程萬里 (붕정만리, péng chéng wànlǐ, ほうてい-ばんり) big bird / jouney / ten thousand / miles

A large bird travels ten thousand miles.

Jang-ja (莊子, 字: 周) of Taoist school (道家) during the Warring States period wrote the following narrative in his Enjoyment in Untroubled Ease (逍遙遊):

There is a large fish named Gon (鯤) living near a corner of the North Sea. It is not known how many ri (approx. a quarter mile) in length it is. It transforms into a bird called Bung (鵬). The size of Bung is also not known. When it spreads its wings to fly, it covers the clouds of the sky with its wings, and it stirs water of the sea. It can fly from one end of the North Sea to the other end of South Sea in one breath. According to a story by Jehae (齊諧) it rides over the whirlwind of 3,000 ri and travels 90,000 ri without a rest, and then folds its wings in to take a rest.

Jang-ja had envisioned a world where both nature and self become one in harmony (物我一體). He had mentioned this bird to metaphorically describe the appearance of a great person who moves around in the freedom of an ideal world that goes beyond the mundane.

From the mention of this, we have words like bung-gon (鵬鯤), or gon-bung (鯤鵬) which signifies something large that is beyond what anyone can imagine. And bung-bae (鵬背: the back of Bung), or bung-ik (鵬翼: the wing of Bung) are used to refer to anything that is very large. Bung-ik is often used to describe airplanes. And words like bung-bak (鵬搏: the flapping of Bung’s wings), bung-bi (鵬飛: the flying of Bung), bung-geo (鵬擧: the rousing of Bung) all describes an act or spirit of achieving something with a great effort or initiative. Bung-do (鵬圖: the picture of Bung) means a great plan or aspiration.

原: 論語, 衛靈公

子曰:「人無遠慮,必有近憂。」

人無遠慮 必有近憂 (인무원려 필유근우,rén wúyuǎnlǜ bì yǒu jìn yōu,ひとぶえんりょしんゆうきんゆう)

If a person does not think far ahead, then he will inevitably experience worries nearby.

This is similar to a saying, “One ought to think deeply of what may happen in the future (深謀遠慮)” from The Critique of Jin (過秦論), an essay written by Ga-eui (賈誼).

Related to this saying, there is a Korean narrative about a civil official (文臣) named Heo Jong (許琮) during the reign of King Seong-jong (成宗) of Joseon dynasty. The Queen Consort was found to be temperamental and was eventually deposed. (She is known as the Deposed Queen Yun (廢妃 尹氏) to this day in Korea.) With the increased pressure from officials, she was later sentenced to death by poisoning. In order to draft this decree to poison (賜死) the deposed Queen, King Seong-jong had summoned all court officials (群臣會議). Heo Jong was a Right Minister (右贊成) at the time, so he had to attend the meeting as well.

While on his way to the royal court, he visited his older sister’s house, and his sister said to him, “How could anyone attend a meeting to poison the Queen? I’m troubled by this. If, at a commoner’s house, the servants gathered to participate in the poisoning of the lady of the house, and her son becomes the head of the household later, what would happen to those servants? How could there be no trouble in the future for them?” He came to realize this, and while passing a bridge, he intentionally fell from the bridge. He excused himself from the meeting due to injuries, and returned home.

Just as his sister had predicted, when King Yeonsan (燕山君) came into power and found out about his mother’s death, he unleashed his wrath against all those involved in the infamous purge of 1504 (甲子士禍). Since then, people started calling that bridge, from which Heo Jong fell, “The Bridge where Heo Jong Fell (琮琛橋)”.

A marker stone over where the bridge was stands in front of Se-yang Building, in Jongro-gu Naeja-dong, Seoul

原: 唐書, 房玄齡傳; 觀政要, 君道; 資治通鑑, 等等

創業守成 (창업수성,chuàngyè shǒuchéng,そうぎょう-しゅせい) start [of] work, maintain or protect / act of

Short form of 易創業難守成, which means the start of a work is easy, but maintaining it is difficult.

During a chaotic time, near the end of Su (隋) dynasty, Yi Yeon (李淵) and Yi Se-min (李世民), who were father and son, raised an army to defeat Emperor Gong (恭帝) of Su and founded the Tang (唐) dynasty in 618 AD.

In 626, King Tae-jong (太宗), named Yi Se-min, succeeded his father, King Go-jo (高祖), named Yi Yeon, and ushered in an age of great prosperity (盛世) under the era name of Jeong-gwan (貞觀之治, 627-649). He unified the country, expanded the territory, guarded against extravagance, stabilized the economy, recruited talents from abroad, and helped to develop the academia and the culture of the country. He became the model king for subsequent kings to follow.

Such Jeong-gwan rule was possible not only because of King Tae-jong’s abilities, but around him were wise retainers such as Du Yeo-hui (杜如晦) who was known for his decisiveness; Bang Hyeon-ryeong (房玄齡), recognized for his planning skills; and Wi Jing (魏徵), known for his upright character.

One day, King Tae-jong asked his retainers, “Between starting a business, and maintaining that business, which is more difficult?”

Bang Hyeon-ryeong replied, “Starting a business can only be achieved by only successful person among many rival leaders that spring up everywhere, so I would say starting is more difficult.”

Wi Jing gave a different reply, “From the old days, the position of a monarch is finally obtained after going through much hardships, however it is easily lost in complacency. Therefore, I think protecting and maintaining is more difficult.”

King Tae-jong nodded, and said, “Duke Bang had to risk his own life with me to gain the whole world, and that’s why he said starting a work is more difficult. Duke Wi has always been cautious against pride and extravagance for the prosperity and the welfare of people (國泰民安), and also against complacency which causes calamity and chaos (禍亂). And that’s why he has said protecting and maintaining is more difficult. Since the difficulties of a start has come to an end, I shall now focus on maintaining with you.”

As recorded in the Royal Annals of Joseon dynasty, June 19, 1625:

傷時歌

嗟爾勳臣

毋庸自誇

爰處其窓

乃占其田

且乘其馬

又行其事

爾與其人

顧何異哉

Lamentation over the current state of affairs

We lament over thee, royal officials

Do not boast about yourselves

You live in their houses

You took over their lands

You ride on their horses

You do what they did

[Between] you and them

[Looking over] what difference are there?

原: 論語, 述而/11

子謂顏淵曰:「用之則行,舍之則藏,唯我與爾有是夫!」

子路曰:「子行三軍,則誰與?」

子曰:「暴虎馮河,死而無悔者,吾不與也。必也臨事而懼,好謀而成者也。」

暴虎馮河 (포호빙하,bào hǔ píng hé,ぼうこ-ひょうが) hit with bare hands / tiger / walk across water / river

Attack a tiger with bare hands and cross a river without anything.

One day, Gong-ja said to his disciple An-yeon (顏淵: 顏回), “Doing the right thing when appointed to an office, and living contently in seclusion when abandoned, are these things only you and I are capable of doing? Gong-ja said this because An-yeon was one of his favorites among over 3,000 disciples. An-yeon was both virtuous and studious, and Gong-ja even fell into a deep despair when he later died at the age of only 31. Gong-ja was praising him with such a comment.

Then, Jaro (仲由), hearing this, became little jealous and asked Gong-ja, “If you were to lead a great army (三軍), who would you have on your side?” Jaro asked this question because he felt himself to be more brave than many. He was sure that Gong-ja would pick him, but the reply was that Gong-ja would not be with someone would be so rash to attack a tiger with bare hands and cross a river without anything. He would rather have someone who thinks deeply about the action to take, and then succeeds in execution of the plan. Gong-ja replied this way to warn him against being rash.

Gong-ja taught it’s difficult to accomplish anything without a good plan, and it can also become prone to failure without being cautious. Jaro became silent at this point.

A passing thought around the use of 子 as a form of honorific: In the Bible, we have the Hebrew conception of the son of man (ben-adam), often applied to Jesus in the New Testament. From a Christian theological perspective, that is used to emphasize a part of his identity as a man, with a respect. In Literary Sinitic, the character for son (子) is used as a form of honorific as in 孔子, 莊子, 荀子, 孫子, etc. There’s also the superlative honorific form 夫子 as in 孔夫子. It is usually applied to an accomplished teacher who has created a new school of thought, or to someone who has simply left a legacy or scholarly works deserving respect. Anyway, I found it interesting that in both, this word, “son,” is used to denote respect. Of course, by its very nature of the meaning of the word, there’s the sense of continuity and connection to our own early forefathers, thereby also implying another form of horizontal connection between the teacher in question and the rest — that we are all related as a big family. The emphasis on personhood seems somewhat related to the concept behind the use of the word 仁, which is often taught as the very core of Confucianism. The etymology may be related to two characters representing person as in 人人, which says a person ought to be a person, in qualitative terms. Again, the main point here is not a mere person, but a virtuous person. Even the Latin root word, vir, from which we have virtue, means a man, or a person. It’s essentially saying the same thing as 人人 is. I don’t know if we have a continuity of such understanding in the use of these words in modernity, but it’d be interesting to find any culture that may have continued in this type of tradition.

原: 孔子家語, 三恕/4 中

孔子曰:吾聞宥坐之器,虛則欹,中則正,滿則覆。

有坐之器 (유좌지기,yǒuzuòzhīqì,ゆうざの-き), nearby [of] bowl

Moderation in all things. Heart should not be emptied nor be overflowing.

Gong-ja was visiting an ancestral shrine (祠堂) of Hwan-gong (桓公) of the country of Ju (周). Inside was a bowl (儀器) used in ritual ceremonies, and it was fixed in a way so that it could tilt freely. Gong-ja asked the keeper of the shrine, “What is this bowl for?” And he replied, “It is a bowl you always look at nearby (有坐之器)” At this, Gong-ja nodded and said, “I did hear about the bowl. It tilts to the side if it’s empty, and it stands upright only if it has just enough water, and if it’s completely filled, it would spill over.”

原: 武信君 蒯通傳, 史記, 後漢書 等等

金城湯池 (금성탕지,jīnchéng tāngchí,きんじょうとうち), metal fortress boiling pond

A word to refer to an impregnable place or thing

Emperor Si-hwang (始皇帝) of Jin (秦) had unified the kingdoms, but it started to decline soon after his death. The families (宗室) and those who had served (遺臣) in old kingdoms rose up to overthrow Jin. Many claimed to be a king in their own right, and the governing system of Jin (郡縣制) was being dismantled completely. It was during this time a man named Mu-sin (武信) had subdued the old territory of Jo (趙) and people called him Lord Mu-sin (武信君). Koi-tong (蒯通), an unappointed advisor (論客), saw all this take place, and told Seo-gong (徐公), a ruler (縣令) of Beom-yang (范陽), that the disgruntled people under his rule are about to rise up against him. Seo-gong asked what Koi-tong had in mind, and Koi-tong said that he will go to Lord Mu-sin and convince him that he should make a good example of how someone who surrenders to him would be treated by accepting your surrender, and treating you with extremely generosity. The logic was that if Seo-gong surrendered and he was treated poorly, other fortresses with become even more impregnable (金城湯池) in defending their places. So, that way, Lord Mu-sin will not suffer loss of war, and others will see how you were treated, and instead of suffering great losses themselves, they will find that it’s better to surrender. Seo-gong sent Koi-tong to Lord Mu-shin. Lord-Mushin, amazed at the wisdom of Koi-tong, invited Seo-gong with the utmost respect and had him go abroad to tell people of this. People of Beom-yang was spared from a war, so they praised Seo-gong, and other regions hearing of this also surrendered to Lord Mu-sin. It is said that over 30 fortresses had surrendered in the region of Hwa-buk (華北) alone.

原: 春秋左傳, 哀公, 哀公十一年/2 中

曰,鳥則擇木,木豈能擇鳥

良禽擇木(양금택목,liáng qín zé mù,りょうきんたくぼく), good bird chooses tree

A wise person chooses a person or a place that recognizes and will help to cultivate his talents.

While Gong-ja (孔子) was staying in the country of Wi (衛) Gongmun-ja (孔文子, 孔圉) came to inquire him about his plans to attack Dae-suk-jil (大叔疾), but Gong-ja replied that he has learned about ancestral rites, but he know nothing about waging wars. Immediately, after, he told his disciples to get ready to leave Wi soon. Hearing about this, Gongmun-ja quickly came back to explain he didn’t have other ulterior motives and pleaded him to stay. At this, Gong-ja decided to stay longer, but a person from the country of Noh (魯) came to implore him to come back and he went back to his home country.

Before taking on a job to work for any company, or stay at any place, it’s a worthwhile effort to consider what type of place it is. If it’s a rotten tree that will fall by itself soon, or if it’s a small branch that won’t be able to withstand the weight of your nest, then it’s better not to settle down from the start.

原: 論語, 八佾/8

子夏問曰:「『巧笑倩兮,美目盼兮,素以為絢兮。』何謂也?」子曰:「繪事後素。」曰:「禮後乎?」子曰:「起予者商也!始可與言詩已矣。」

繪事後素(회사후소,huìshìhòusù,かいじこうそ), painting work after white

Horse before carriage. Essentials or canvas come first before formalities or decorations.

This is from a passage where Gong-ja reminds his disciples that a person ought to develop his character first before adding on other stylistic things (文飾).

Jaha (字: 子夏, 卜商) asked, “What does this text mean? ‘Dimples from a beautiful smile are pretty, pupils from beautiful eyes are clear. It is like painting with white silk (素以爲絢).'” Gong-ja (孔子) replied, “You paint after you prepare a white canvas (繪事後素).” To which, Jaha asked again, “So etiquettes/formalities (禮) come after?” And at this, Gong-ja expressed his great pleasure with Jaha’s reply and said that he is now ready to discuss poetry (詩).

Jaha realized that formalities (depicted as a painting (絢)) are expressions of the heart (depicted as a white canvas (素)), and the principle of poetry is the same. This is why Gong-ja praised his reply, and considered him ready to discuss poetry.

The mainstream interpretation of this was reinforced by Zhu-ja (朱子, 朱熹, 1130-1200) of Song (宋) dynasty, but a different interpretation was given earlier during later Han (漢) dynasty by Jung Hyeon (鄭玄, 127-200) who read this as painting white (素) after painting with colors (繪), so as to filling in the spaces between colors with white.

原: 列子, 湯問

太形、王屋二山,方七百里,高万仞。本在冀州之南,河阳之北。北山愚公者,年且九十,面山而居。

愚公移山(우공이산,yúgōngyíshān,ぐこういざん), Wu-gong moves mountains

No matter how difficult, it can be done with persistence and diligence

There lived a 90-year old man named Wu-gong (愚公) whose residence was between two tall mountains, Mt. Tae-haeng (太行山) and Mt. Wang-ok (王玉山). He’s always found it difficult to travel to and fro other towns, so he gathered his family members to discuss creating a level road all the way to Ye-ju (豫州) and south of Han-su (漢水). However, his wife objected saying how an old man like him would be able to remove the dirt from the mountain and where to put the dirt, and to this, he replied nonchalantly, “I’ll just dump it in the Bohai Sea (渤海).”

Soon, Wu-gong with his three sons and grandsons started working. It was no easy task, since the travel to dump dirt at Bohai Sea would take a year. One day, an old friend Ji-su (智叟) tried to persuade Wu-gong to stop the work because of the age. To this, Wu-gong simply replied that his sons will carry out the work, and then his grandsons, and then later generations will continue the work until two mountains disappear. Ji-su went away shaking his head, however, the mountain spirit (蛇神) guarding those two mountains were shocked to hear this, and reported this to the Jade Emperor (玉皇上帝, aka God of Heaven). He was moved by Wu-gong’s persistence, and ordered to relocate Mt. Tae-haeng to Sak-dong (朔東) and Mt. Wang-ok to Ong-nam (雍南).

(蛇足: This is why they say there used to be two mountains in Gi-ju (冀州) but nowadays, there is not even a small hill there.)

原: 論語, 里仁/15

子曰:「參乎!吾道一以貫之。」曾子曰:「唯。」子出。門人問曰:「何謂也?」曾子曰:「夫子之道,忠恕而已矣。」

原: 論語, 衛靈公/3

子曰:「賜也,女以予為多學而識之者與?」對曰:「然,非與?」曰:「非也,予一以貫之。」

一以貫之(일이관지), one [/with] through/[threaded] — understanding many through one or a grand principle

From Yi-in (里仁): Gong-ja (孔子) said, “Sam (參, 曾子), my way is through only one thing.” To which, Jeung-ja (曾子) replied, “Yes, indeed.” After Gong-ja left the room, literati (門人) asked Sam what the master meant. Jeung-ja answered, “My master’s way is only of faithfulness (忠, as being wholehearted) and compassion (恕, as in compassionate understanding of others).”

From Wi-ryeong-gong (衛靈公): Gong-ja asked Sa (賜, 字: 子貢), “Do you see me as someone learned in many things, and be able to recall them well?” Ja-gong (子貢) replied, “Yes, are you not?” Gong-ja answered, “No, I merely see all things through one.”

It’s debatable as to what this penetrating through one thing (一以貫之) may truly mean, but one way to understand this is that, as already mentioned, faithfulness and compassion is a mere way to achieve this, and looking through the greater context it’s only natural to interpret humaneness (仁) as the way (道) through which all things can be reflected on.

原: 孔子家語, 三恕/10

子曰: 由!是倨倨者何也?夫江始出於岷山,其源可以濫觴 …

濫觴 (남상), [enough to] run over a small glass [for liquor]

A warning to disciple, Jaro (仲由, 字: 子路), who once showed off a fancy dress. Gong-ja (孔子) reminded him that the source of a great river Yang-ja (楊子江) is no more than enough to run over a small glass.

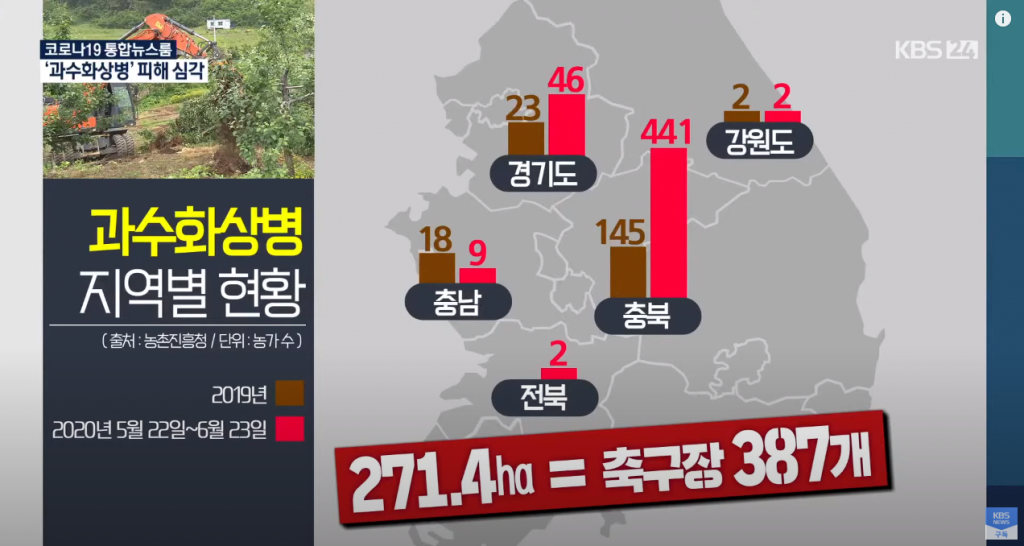

果: 실과 과

樹: 나무 수

火: 불 화

傷: 다칠 상

病: 병 병

日: かじゅかしょうびょう (kajyu kashōbyō)

中: 果树 [guǒshù] 火伤 [huǒshāng] 病 [bìng]

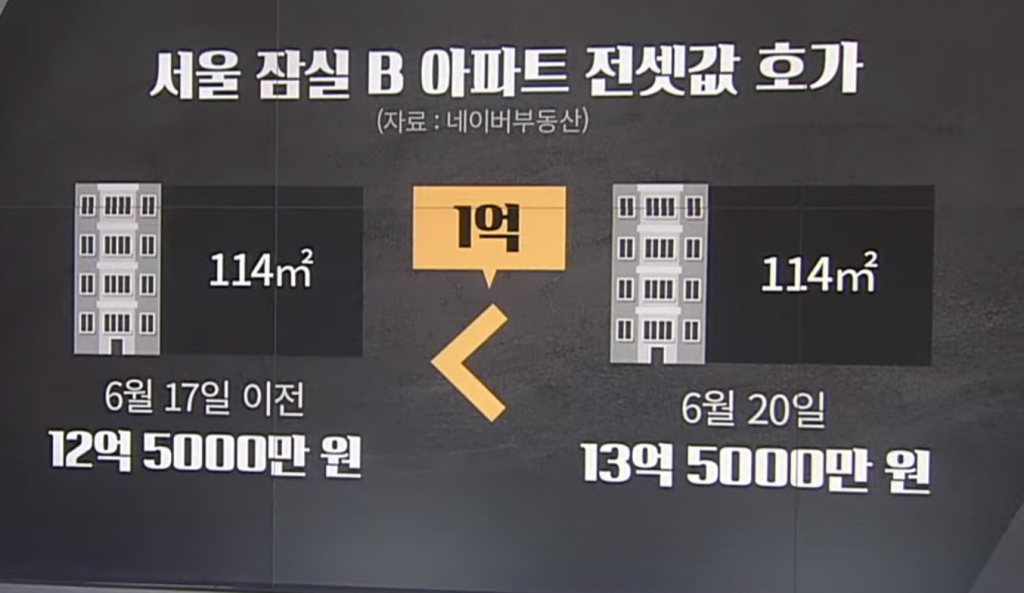

호가 (호까)

呼: 부를 호

價: 값 가

팔거나 사려고 물건(物件)의 값을 얼마라고 부름

日: よびね [yobine], 中: 叫价 [jiàojià]

屌丝

屌: 자지 조

絲 (丝): 실 사

중국어 [신조어] 돈도 없고, 외모도 별로고, 집안 배경도 없고, 미래도 어두운 사람

실패자, 찌질이

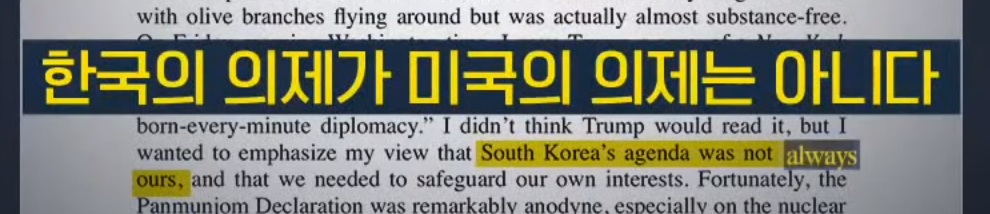

의제:

議: 의논할 의

題: 제목 제

의논(議論)할 문제(問題)